|

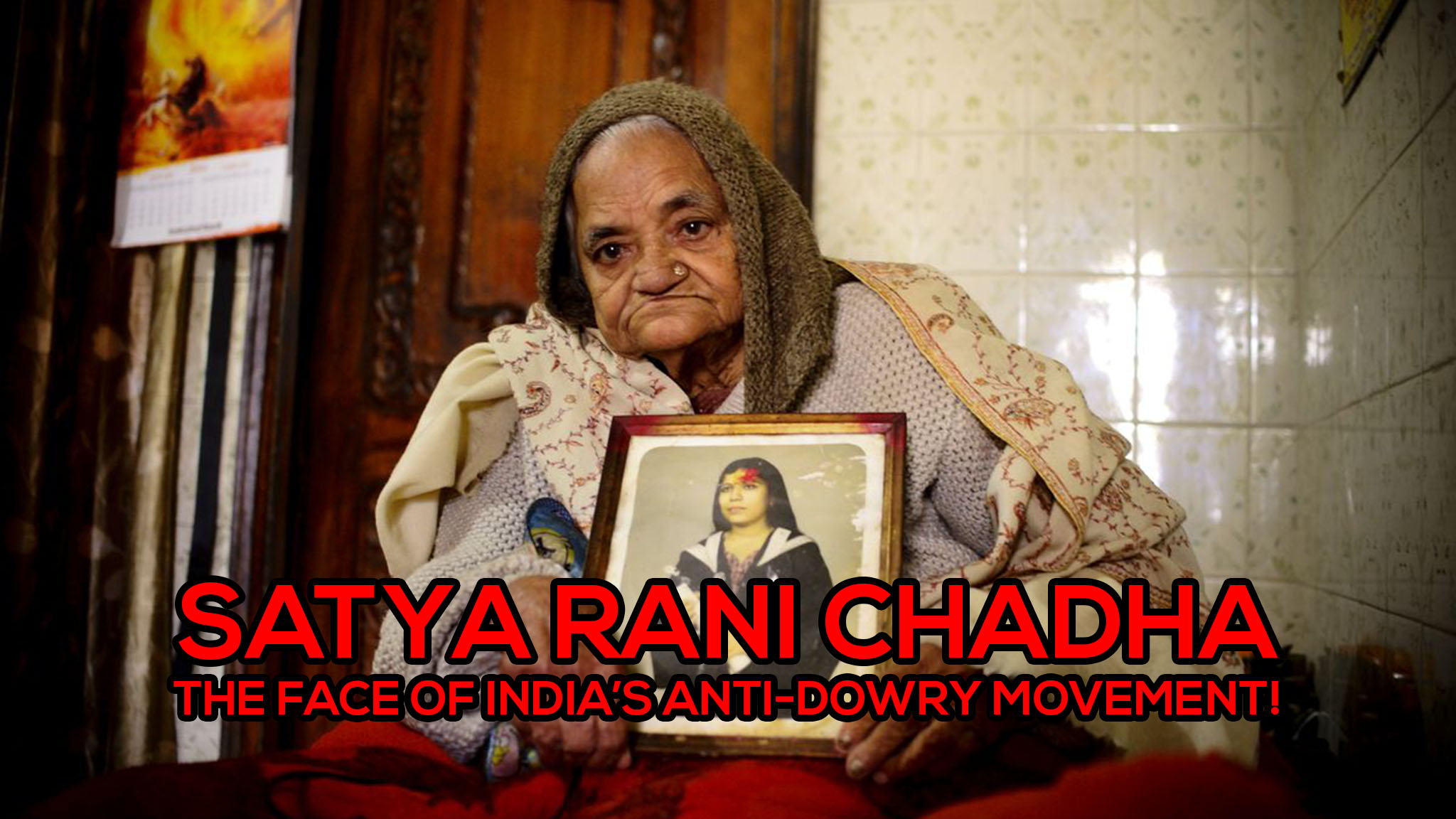

| Satya Rani Chadha holding a picture of her daughter Shashi Bala. |

Why are there dowries? Because in Indian society a girl is considered a liability. Since she is not an equal of man, her father has to give dowry to her groom to make up for her inferiority. Fathers often become indebted for life if they have more than one daughter to marry. Dowries have not only increased in recent years but created new and alarming problems of suicide and murder.

It is bad enough that a girl should be bartered and sold as a commodity.

It is worse when the demands continue after her marriage. If her

parents do not provide what their son-in-law or his family ask for,

their daughter can be beaten or murdered. (in which case the boy becomes

free to remarry). In most cases the dowry the boy receives is used to

marry off his sisters, perpetuating a vicious circle. In recent months

an increasing number of cases have come to light in Delhi about the

burning of brides. One government hospital registers about 4000 burn

cases a year, of which 75 per cent are women. Hospital authorities

suspect that 9 out of 10 of these are dowry burns or deaths.

Though the anti-dowry movement in Delhi is spearheaded by three women’s organisations – Mahila Dakshata Samiti, Nari Raksha Samiti and Istri Sangharsh Samiti – unfortunately there is little coordination between them. When cases of harassment are brought to their notice, at first they try for a compromise. Mrs Krishan Kant, who heads the antidowry cell of the Mahila Dakshata Samiti, described one such effort: ‘I made it clear to the girl’s motherin-law that from now on we would be the girl’s guardians and take necessary action. It had the desired effect; the illtreatment stopped. Fear of scandal makes many families behave.

If a girl dies and foul play is suspected, these organisations try and create public opinion through the press so that the case is investigated by the police instead of being hushed up.

However, nothing is as effective as social boycott of families where girls are illtreated or where murder is suspected. In the case of 24-year-old Tarvinder Kaur (who made a dying statement that her mother-in-law had poured kerosene over her clothes and her sister-in-law had set her alight and yet the police registered it as a case of suicide) – women of Delhi marched through the middle-class colony where she was burnt to death. Punish the murderers of Tarvinder, they demanded.

Later these students, teachers, working women and housewives marched to Parliament where they presented a memorandum to the Home Minister asking for reforms in the marriage and dowry laws.

Nearly 34 years (May, 2013) after her daughter’s murder, Satya Rani Chadha had won in court. But there was no solace for her.

Mahila Dakshata Samiti, 2 Telegraph Lane, New Delhi 110001, India.

Source of Story